A recent study put forth by Barna research discussed the current “State of Discipleship.”[1]

I’m a big discipleship advocate—constantly preaching and teaching about the Great Commission, mission, and disciple-making. Not only do I preach and teach it—I disciple and invest into others. I love relational community.

But, the Western church is hemorrhaging. I believe the number one reason is a lack of disciple-making. Barna reveals, “only 20 percent of Christian adults are involved in some sort of discipleship activity.”

In the research, Christians were asked which term or phrase best described a spiritual growth process. Ironically, but very illuminating, “discipleship” ranked fourth on the list—being selected by fewer than one in five Christians (18%).[2] That’s disturbing. Only one in five Christians equated the term discipleship with spiritual growth. It seems that something is amiss within the contemporary church.

Spiritual Growth is Great?

Barna’s numbers seem contradictory. Only 25 percent of the polled respondents stated discipleship was very relevant. The research indicated “The implication is that while spiritual growth is very important to tens of millions, the language and terminology surrounding discipleship seems to be undergoing a change, with other phrases coming to be used more frequently than the term ‘discipleship’ itself.” So, the dilemma within discipleship is the fact that a majority of Christians do not equate themselves with disciples.

I found it ironic that 52 percent who attended church in the past six months, asserted that their church “definitely does a good job helping people grow spiritually,” while 73 percent believed their church places “a lot” of emphasis on spiritual growth. How can that many believers think their church is doing a good job at growing spiritually, and yet the church is not making disciples?

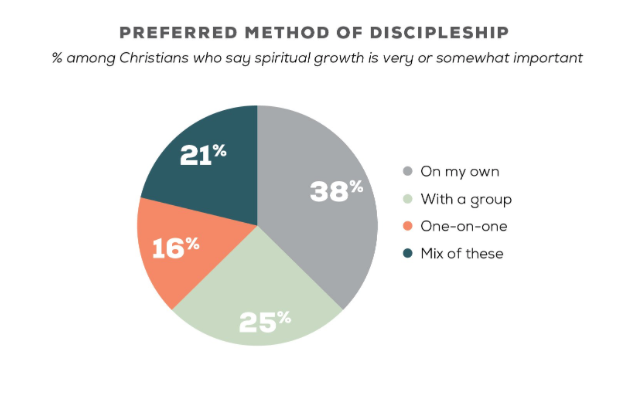

The problem is the perceived definition of spiritual growth and its relationship to disciple-making. It seems that a majority of Christians view spiritual growth as an individual construct—as if discipleship can be divorced from Christianity—it’s in a vacuum. Nearlytwo out of five of all Christian adults consider their spiritual growth to be “entirely private.”

The Real News

Disciple-making is about reproducing—making other disciples. If 73% of the polled believers stated that their church places a major emphasis on spiritual growth—why is the church not making disciples?

Why is the church severely declining—with 80 to 85 percent of all Western churches in decline or stagnating?

I believe it has to do with perception. In the article, Barna stated that only 1% of church leaders believed their churches were discipling very well. That’s only 1%—one—uno—eine—en—no matter what language— just 1% believe their church is discipling very well. Opposite of doing well—60 percent (60%) of pastors state the church is not discipling well, at all!

Why would that be? Don’t three out of four Christians believe their church places a major emphasis on spiritual growth? Why the disparity?

As a pastor, I believe it’s because we (pastors) correlate discipleship with relational communion—life together. Barna’s poll revealed that 91% of pastors considered “a comprehensive discipleship curriculum” as the least-important element of effective discipleship. Yet, when polling Christians, a perception of discipleship, or spiritual growth is related to curriculum, class, and study—not relational connectivity and with-ness.

Barna notes “Only 17 percent say they meet with a spiritual mentor as part of their discipleship efforts.” That’s it! This is why the church is not growing and this is why the church is failing at making disciples. The majority of Christians do not see relational communion with others as important. And discipleship pertains to personalized spiritual disciplines.

How Did This Happen?

There’s a logical explanation—but not a quick one.

Perhaps due to infant baptism, from the fifth-century, and continuing into the Reformation period, discipleship progressed toward individual spiritual discipline more than communal interactive relationships concerning the daily rhythms of Christian life.

While catechesis still existed for new converts, the continued practice of infant baptism shifted discipleship away from the convert catechumenate (waiting three years prior to baptism, but partaking in communal life) to spiritual disciplines and devotions of individualized believers.[3] Perhaps the most notable reformer, Martin Luther, believed that discipleship guided the believer into deeper devotions toward Christ.[4] For Luther, discipleship referred to Christ’s inner working power and “not our attempts to imitate” the deeds of Christ.[5]

The early church had communal gatherings for fellowship, teaching, and life-on-life. But, due to ongoing heretical views—the church began to focus more on the individual development of personal character and devotion, along with theological and doctrinal polity. Albeit, Luther’s discipleship consisted of a deeper commitment to the spiritual devotions of prayer, fasting, and the Word of God, it was not communal.

John Calvin described discipleship as an automatic title for the regenerated believer, an identity by grace in Christ.[6] Calvin, a paedobaptist, considered all believers disciples (and I agree), but not in the same aspect of the communal spiritual nourishment, as that of the early church. For Calvin, baptism became the sign and ratified seal of a “professed” disciple (I find an infant professing anything as odd).[7] However, Calvin focused more on knowledge transference, with believers hearing the preached Word, than a day-to-day activity with believers who practiced fellowship-style catechesis and breaking of the bread (Acts 2:42–46).[8] But to his credit, Calvin believed that all Christians should carry out the commission of God within their lives.[9]

So, the problem was an eventual drifting from the early church communal relationship instruction and fellowship to a more individualized spiritual discipline-type formation. So then, you can see, for the contemporary Christian, discipleship is perceived as curriculum, not as much associated with communal spiritual growth. Discipleship became divorced from collective spiritual maturity, because it became divorced from the communal gathering and growth with others.

The solution calls for reverting back to the origin of Christ-following and being a relational disciple-maker of Christ. Disciples make disciples. Discipleship is not merelyspiritual growth, but helping others, relationally, to develop into mature disciples, who make disciples, etc.